by Michael J. McGuire

I have been intrigued by the term “pure and wholesome” throughout my career. After I came upon it during my research for The Chlorine Revolution, I knew that I had to learn more about it. One of the best descriptions of what pure and wholesome meant at the turn of the 20th century was given in the context of two trials about water quality in Jersey City, New Jersey. (McGuire 2013)

The Jersey City Trials

In 1899, Jersey City, New Jersey signed a contract with a private water company to build a new water supply on the Rockaway River to supply up to 50 million gallons per day. Included in the contract were requirements to build a large dam, create a reservoir holding seven billion gallons and construct a 23-mile pipeline-tunnel conveyance to transport the water to the City. The contract specifically required that the water delivered be “pure and wholesome.” No treatment was provided for the water except the clarification and opportunity for bacterial die off provided by the detention time in the reservoir.

Delivery of water from Boonton Reservoir began on May 23, 1904. However, the City was not happy with the quality of the water or the price that they would have to pay for the water works. They filed a lawsuit against the private water company that resulted in two trials. The first trial focused on the bacterial quality of the water and how that quality stacked up against the requirement that the water must be pure and wholesome. The contract language was very specific.

“‘The water proposed to be furnished is pure and wholesome. The plan has been prepared so as to prevent all contamination thereof from any source in accordance with the specifications.’

The specifications provided as follows:

‘The water to be furnished must be pure and wholesome for drinking and domestic purposes.’” (Stevens 1908)

The judge’s opinion from the first trial made clear his definition of pure and wholesome.

“Again, the requirement that the water must be pure and wholesome does not mean that it shall be absolutely pure—of such purity as could be obtained in a laboratory—all that is required is that it be ‘free from pollution deleterious for drinking and domestic purposes.’” (Stevens 1908)

The Company tried to define pure and wholesome by showing that the typhoid fever death rate in Jersey City was now much lower than the typhoid death rates in other cities. The judge acknowledged the improvement in Jersey City typhoid statistics but stated that the contract language was most important, “In the case in hand Jersey City bargained, not for water less polluted than that of some other cities, but for pure and wholesome water.” (Stevens 1908)

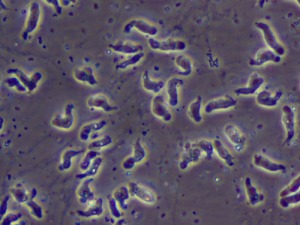

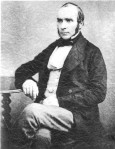

At the end of the first trial, the judge agreed with Jersey City that two or three times per year, the delivered water had high bacterial counts and did not meet the standard of pure and wholesome established in the contract. A second trial was held under the authority of a Special Master. Between the two trials, John L. Leal who worked for the private water company installed a chlorination system to kill the bacteria that resulted in the project’s water being labeled as impure and unwholesome. The purpose of the second trial was to determine if the use of chlorine was safe, reliable and effective. Most importantly, the second trial was to determine if the standard of pure and wholesome was met when chlorine was used.

On May 9, 1910, the Special Master filed his report, which was a victory for the private water company and for the use of chlorine to kill bacteria that contaminated drinking water.

“I do therefore find and report that this device [chlorination] is capable of rendering the water delivered to Jersey City, pure and wholesome, for the purposes for which it is intended, and is effective in removing from the water those dangerous germs which were deemed by the decree to possibly exist therein at certain times.” (emphasis added, Magie 1910)

The usage of the term in this lawsuit seemed to be clear, but I was not satisfied. I wanted to know where the term came from, did it describe safe drinking water and did its definition change over time?

Pure and Wholesome Through the Ages

The first use of “pure and wholesome” is lost in the dim mists of history. However, it is likely that humans have used the concept embodied in the term since the beginnings of the written record. There are numerous examples of the use of the term in religious tracts, literature, scientific writings and news items. It is also clear from the early references that people were defining pure and wholesome based on their senses of sight, taste, smell and touch (feeling).

An important portion of the Koran (or Quran) related to diet has been translated many ways. One of alternatives is: “Eat (as lawful, pure and wholesome) from that which God has provided for you; and keep from disobedience to God, in Whom you have faith.” (emphasis added, Islam Awakened 2013)

In a discussion of the Torah, the concept is raised. “‘And Yaakov went out’ – This seemingly innocent opening of our Parasha is really not as simple as it may appear. Think about it: From where is Yaakov going out and where is he going to? He is departing from Yitzchak and Rivka’s warm home, from the cozy tent (as the verse says, “he dwelt in tents”), from a pure and wholesome environment (and Yaakov was “tam”, meaning wholesome or pure).” (emphasis added, Parashat Vayetze 2001)

An early Roman Catholic blessing for a water well contains the phrase, but we do not know for sure if this is wording from the early days of Christianity. “Lord God almighty, who so disposed matters that water comes forth from the depths of this well by means of its pipes; grant, we pray, that with your help and by this blessing imparted through our ministry all diabolical wiles and cunning may be dispelled, and the water of this well may always remain pure and wholesome; through Christ our Lord.” (emphasis added, Sancta Missa 1962)

A 16th century philogist and humanist had something to say about the purity of the air. The work was originally written in Latin in 1584 and translated into English in 1594. “Art thou weary of the concourse of people? Here thou mayest be alone. Have thy worldly business tired thee? Here thou mayest be refreshed again, where the food of quietness and gentle blowing of the pure and wholesome air will even breathe a new life into thee.” (emphasis added, Lipsius 1584)

A 17th century use of the term in a religious context was notable. “…as there, the nature of the most pure & generous wine is described, whereby men are allured to drinke thereof; so here the right wine, the pure and wholesome doctrine out of the mouth of the Spouse, is declared by the company of Beleevers, to be pleasing and right…” (Ainsworth 1639)

In the 17th century, a topographer described the various winds that existed on the earth. “The East wind is very hot, and intemperately dry; yet very pleasant, pure and wholesome: (but chiefly in the morning) for it preserves the body sound, and in winter it produceth frost.” (Porter 1661)

One hundred and fifty years before the germ theory of disease was espoused, one author in 1718 tried to explain how the cleanliness of air and water were related.

“The Ancients, among the admirable rules delivered by them for the choice of water, frequently inculcate its similitude to air; partly on account of the greater lightness and purity of the finest waters, and partly on account of the changes wrought in them both by their stagnation, and mixture with heterogeneous particles. And indeed, as there is nothing that contributes more to render the air pure and wholesome, than its agitation by winds and gentle breezes; so neither does any thing preserve water from corrupting, and acquiring the most mischievous qualities, so well, as a brisk and rapid motion, which is so essentially necessary to this end, as to be constantly enumerated amonst (sic) the distinguishing characters of a wholesome water.” (emphasis added, Wintingham 1718)

In the early 19th century, a discussion of the Albany, New York, water supply made it clear that a good quality of water was needed to serve the City. “The importance of a constant and certain supply of pure and wholesome water, to the inhabitants of populous towns, can hardly be duly appreciated, and there is little danger that it should ever be overrated.” (emphasis added, Albany 1815)

A few years later, an author related the quality of the water based on its passage through soil. “Nature also compels the motion of this invaluable fluid through the bowels of the earth, and by various efforts, of which those of gravity, however, are the chief; thus effecting a most perfect filtration, and converting water, such as had even been derived from the most putrid supplies, into a beverage the most delicious, the most refreshing, and found generally to be perfectly wholesome.” (emphasis added, Berenger 1828)

In the 17th and 18th centuries, New York City struggled to find a reliable, safe water supply. Polluted wells and a grossly contaminated pond (the Collect) in southern Manhattan provided an inadequate water supply with the side benefit of providing death from cholera and typhoid fever. After much political maneuvering, Aaron Burr was able to get the state legislature to confer on the Manhattan Company the exclusive right to supply the City “…with pure and wholesome water.” (Blake 1956)

Pure and wholesome also figured in the early history of the Detroit water system. Rufus Wells built the first organized City water system on the banks of the Detroit River. The private water company supplied Detroit between 1827 and 1836. In 1836, the City purchased the water works from Wells for a reduced price of $20,500 as a result of his company not providing an adequate flow of water that was “clear, pure and wholesome.” (emphasis added, Daisy no date)

In the latter half of the 1800s, Rochester, New York, needed a new water supply, so they approached the state legislature for the authority to do so. “The result was the passage of the law entitled, ‘an act to supply the city of Rochester with pure wholesome water’ on April 27, 1872. By this act the mayor was directed to appoint five persons to constitute a ‘board of water commissioners,’ who were to ‘examine and consider all matters relative to supplying the City of Rochester with a sufficient quantity of pure and wholesome water for the use of its inhabitants, and for the extinguishment of fires.’” (emphasis added, (Hemlock 2013)

In a 1905 article describing the European practices of water purification, the author discussed the prevalent view that water from the ground, especially spring water, was of the highest quality. “Springs were deified by the ancients and something of this feeling remains, in the belief that they must be naturally pure and wholesome.” He went on to discount this notion due to problems caused by contamination. Even so, the author used the term pure and wholesome to refer to the highest quality, indeed water quality fit for the gods. (Kemna 1905)

As our understanding of disease and toxicology became more sophisticated, the interpretation of pure and wholesome became more complicated. In 1915, sanitary engineer John W. Hill published a paper about the history of the City of Cincinnati water works. In 1865, the City hired James P. Kirkwood who was, perhaps, the most famous water engineer of the time to determine whether a new and expanded water supply was necessary. The Ohio River had a number of quality problems that generated complaints from the users. Kirkwood recommended clarification in large basins followed by filtration using slow sand filters. While none of his recommendations were followed, it is interesting to note Hill’s take on the definition of pure and wholesome that was operative at the end of the Civil War. “In Mr. Kirkwood’s day not much was known of bacterial purification of water and his terms for a pure and wholesome water was that it should be “clear and colorless.’” A filtration plant would not be built in Cincinnati until 1907 and continuous chlorination would start as late as 1918.

As our understanding of disease and toxicology became more sophisticated, the interpretation of pure and wholesome became more complicated. In 1915, sanitary engineer John W. Hill published a paper about the history of the City of Cincinnati water works. In 1865, the City hired James P. Kirkwood who was, perhaps, the most famous water engineer of the time to determine whether a new and expanded water supply was necessary. The Ohio River had a number of quality problems that generated complaints from the users. Kirkwood recommended clarification in large basins followed by filtration using slow sand filters. While none of his recommendations were followed, it is interesting to note Hill’s take on the definition of pure and wholesome that was operative at the end of the Civil War. “In Mr. Kirkwood’s day not much was known of bacterial purification of water and his terms for a pure and wholesome water was that it should be “clear and colorless.’” A filtration plant would not be built in Cincinnati until 1907 and continuous chlorination would start as late as 1918.

In 1907, a famous sanitary engineer, George C. Whipple, wrote a book entitled The Value of Pure Water. In the book, was one of the more complete definitions of pure and wholesome for that time.

“To define the meaning of the expression “pure and wholesome water,” which is so often found in water supply contracts, would seem to be an easy matter, after all the study that has been given to the subject in recent years; but, although every one knows in a general way what is implied by this expression, yet when it comes to framing a definition in positive scientific terms, the problem is not as easy as it seems. This is not because the chemist and the biologist do not know what pure water is, but because water has so many attributes which have to be taken into consideration, and because these attributes vary in importance in every instance. ‘Pure and wholesome water’ is not a substance of absolute quality. Strictly speaking, pure water does not exist in nature; all natural waters contain substances in solution or in suspension; and in proportion as these substances are present, and in proportion as they are objectionable in character, the water is impure. Definitions of pure and wholesome water, therefore, generally state what foreign substances shall not be present, or in what amounts they are permissible….

Unquestionably the term ‘pure and wholesome water,’ as ordinarily used, relates to water intended to be used for drinking. Such a water must be free from all poisonous substances, as the salts of lead; it must be free from bacteria or other organisms liable to cause disease, such as the bacilli of typhoid fever or dysentery; it must also be free from bacteria of fecal origin, such at B. coli. In other words, the water must be free from poisonous substances, from infection, and even from contamination [with fecal matter]. Besides this, it must be practically clear, colorless, odorless, and reasonably free from objectionable chemical salts in solution and from microscopic organisms in suspension. Moreover, it must be well aerated. Color, turbidity, odor, dissolved salts, etc., may be permissible to a small degree without throwing the water outside of the definition of pure and wholesome waters.” (Whipple 1907)

A few years later, authors from the UK took up the task of defining the term based on chemical and bacterial constituents.

“Under the Public Health Act and Waterworks Clauses Act all water authorities are required to provide and keep in any waterworks invested in them a supply of ‘pure and wholesome’ water”… Wholesomeness…is purely a medical question, whilst purity must be physical and chemical. As a physically or chemically pure water does not occur in Nature, and has defied all efforts to obtain it, obviously it signifies ‘hygienically’ pure, that is, a water pleasing to the senses….

We are, therefore, of opinion that water taken from a properly protected river and submitted to a proper system of purification, if it is free from visible suspended matter, free from colour, odour, and taste, free from all bacteria of a type indicating the possible presence of disease-producing organisms,,,and contains no matter of mineral origin which in quality or quantity would render it dangerous to health, is a water which can be properly designated as ‘pure and wholesome.’ The same would apply to water from any other properly protected source, be it well, spring, or surface water….

Turbid waters, or waters containing visible suspended matter, need not be unwholesome, but they are not pure….

A water with any kind of odour should be considered as impure so long as it retains this odour….

A water with an objectionable taste would be decidedly impure, but there are numerous waters with a faint chalybeate [iron] taste, or with a salty flavour about which there might be differences of opinion.” (Thresh, Beale and Suckling 1933)

The article continues with some interesting but contradictory judgments about what was pure and what is wholesome. A new approach that defined safe drinking water was sorely needed to overcome the variations in narrative descriptions of pure and wholesome.

The Rise of Numerical Regulations

The term pure and wholesome had a lot of power 200 years ago. Even though it was not precisely defined, people thought that they knew what they were talking about. As time passed, the meaning of pure and wholesome changed. As shown above, the meaning changed as a direct result of our scientific and engineering progress. In the early part of the 20th century, regulation of safe drinking water took another step. The first U.S. numerical drinking water regulation was established in 1914 when the U.S. Surgeon General through the Department of the Treasury set numerical limits for bacteria in drinking water used in interstate commerce. In the years following, drinking water regulations were expanded to cover more contaminants and strict numerical limits.

The 1962 U.S. Public Health Service drinking water standards were the last ones established by the federal government that only applied to interstate common carriers. The 1974 Safe Drinking Water Act changed everything. The USEPA was ordered to set numerical standards and treatment techniques that ultimately applied to all community water systems in the U.S. through state regulation and primacy.

Thus the general concept of pure and wholesome decreased in importance over time, as we got smarter about the science of water quality. No one uses pure and wholesome anymore, right? Not so fast. The term is included in the California Safe Drinking Water Act and is probably embedded in a number of other state laws on drinking water. The current version of the Act states that water must be delivered that is pure, wholesome, healthful and potable. At a water conference in November 2013, a senior official of the California Department of Public Health, Drinking Water Program, stated that she found the requirement for pure and wholesome water useful because it covered situations that were not specifically mentioned in the numerical regulations. It gave her latitude to improve drinking water quality, and, yes, make the water more pure and wholesome.

A world body was convinced that the term had meaning for the development of requirements for safe drinking water. The author of an article placed in context the narrative and the quantitative requirements of water quality regulations especially with regard to the World Health Organization. “Standards for drinking water supplies were at the same time cast, and perhaps rather curiously so, in the linguistic terms of being required to be ‘pure’ and ‘wholesome’. They were further guided in quantitative terms by definitions of ‘approximate levels [of substance concentrations] above which trouble may arise’ (World Health Organization, 1970).” (Beck 1984)

Google Creates an Amazing Gizmo

The folks at Google have created an astonishingly useful tool called the Ngram Viewer. First you have to understand that Google has scanned over 5.2 million books from a large number of libraries. All of these books are keyword searchable which helped me enormously when I was researching The Chlorine Revolution. So, like all good data geeks, the Google folks created a database of over 1 trillion words (that’s trillion with a T) that were found in books from the year 1500 to 2008. Anyone can analyze this database using the Ngram Viewer created by Jon Orwant and Will Brockman. (Singer 2013)

The user can choose up to five words separated by commas or one phrase of up to five words (or any combination as long as you do not exceed 5) and a graph will be created showing how the word or phrase usage has changed over time. Linguists mostly use the viewer to study esoteric word usage that I certainly do not understand. My friend, Geoffrey Nunberg, finds it useful in his advanced linguistic research.

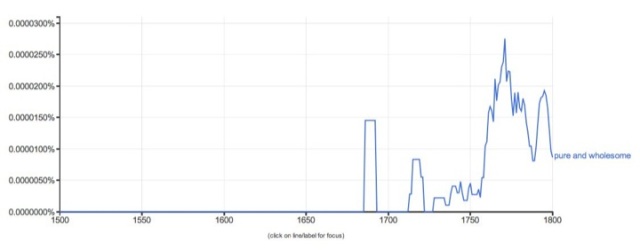

I wanted to find out how far back the term pure and wholesome was used in both British and American English. Information from both variations of the language would be related and helpful.

Figure 1 plots the relative usage of pure and wholesome from 1500 to 1800. By the way, the percent value plotted on the y-axis is the percent usage for that term compared to all other 3-word terms used in any particular year. The number of books scanned before 1800 is relatively small and care must be used in interpreting the graph. For example, it is not necessarily true that the first time that pure and wholesome is mentioned in a book is 1685 as noted on the graph. It is more likely that Google has not scanned any books covering this subject matter before that year.

Figure 1. Relative Usage of “pure and wholesome” in British and American English, 1500 to 1800. (Google 2013)

One of the earliest references to pure and wholesome water using information from this graph was from a medical advice book from 1759. The author uses the term in a manner that seems to indicate that he is quite familiar with its meaning and context.

“Boerhaave, in his elem[entary] chem[istry] [tome]…speaking of snow-water seems at first sight to contradict Hippocrates, and to affirm, that snow water is pure and wholesome.” (MacKenzie 1759)

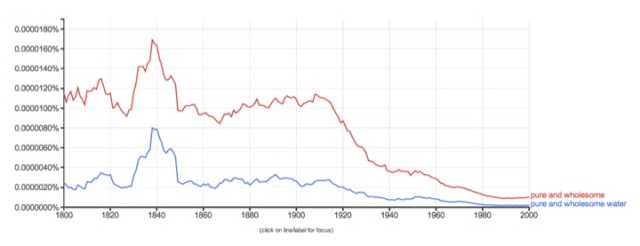

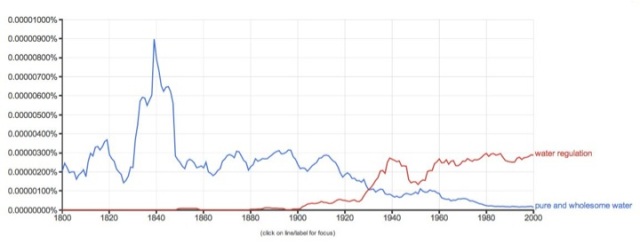

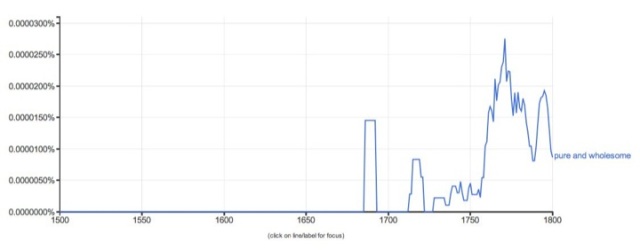

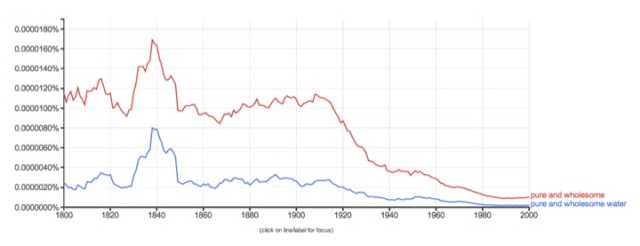

For Google data between 1800 and 2000, Figure 2 shows that the usage of the term pure and wholesome was relatively high and consistent between 1800 and about 1910 except for an interesting bump that peaked in 1840. After 1910, the usage of pure and wholesome drops dramatically until it is little used (relatively speaking) in the year 2000.

Figure 2. Relative Usage of “pure and wholesome” and “pure and wholesome water” in British and American English, 1800 to 2000. (Google 2013)

Also plotted on the graph is the relative occurrence of the term “pure and wholesome water.” The overall term pure and wholesome was used to describe the desired quality of water, air, milk and food. The graph shows that the variation in the relative usage of the two phrases was equivalent over the period shown.

What about the bump? I can only speculate that the dramatic rise in usage of pure and wholesome was triggered by the first cholera pandemic that originated in the Ganges Valley of India and swept through Europe, England and the U.S. before dying out. Newspapers were filled with terrifying stories of the progress of the disease, which struck with fury in England and the U.S. in 1831-32. Successive pandemics plagued the world until the last one in the early 1890s, which was somewhat controlled by strict quarantine regulations. Given the obsession with this disease, it is not hard to imagine that book authors were writing about what was pure and wholesome between 1830 to 1850.

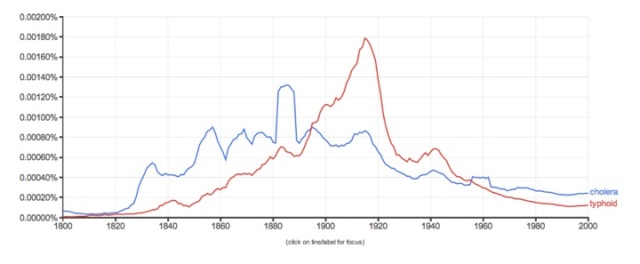

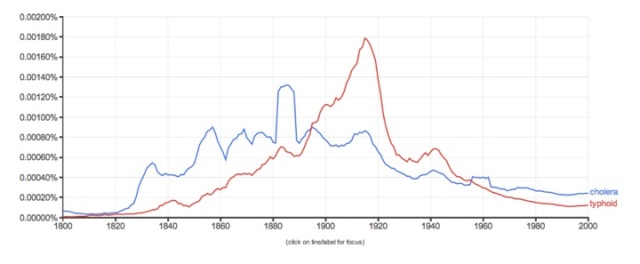

Figure 3 shows that the relative use of the word cholera in books started to drop after 1900, but interestingly, it shows a steady level of low relative usage until 2000. In other words, we are still writing books that mention cholera today. Just think about the disaster that is still unfolding in Haiti if you need a recent example. In some ways, problems with typhoid fever replaced those of cholera in the late 1800s and early 1900s with the peak being reached in 1915. Not surprisingly, mention of typhoid in books began to drop after that year due to the widespread implementation of filtration and chlorination of water supplies.

Figure 3. Relative Usage of “cholera” and “typhoid” in British and American English, 1800 to 2000. (Google 2013)

In reaction to the spectacular threats of cholera and typhoid fever, citizens and politicians alike demanded in the early 20th century that the safety of their drinking water be improved. The Chlorine Revolution is all about how the first use of chemical disinfection in drinking water eliminated the scourge of typhoid fever in the U.S. (McGuire 2013)

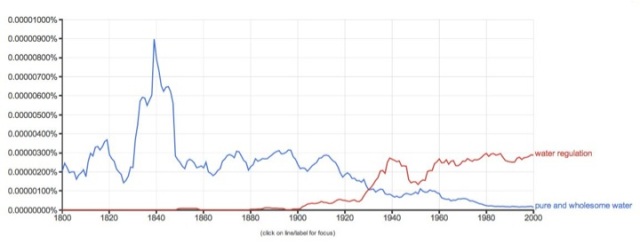

Figure 4 shows that while the relative usage of pure and wholesome water declined from 1910 until 2000, the relative usage of the term “water regulation” increased, beginning about 1900 with a significant increase in usage about 1925. These word-usage patterns may explain what we already know to be true—that specific drinking water regulations began to replace narrative use of the term pure and wholesome beginning in the early part of the 20th century.

Figure 4. Relative Usage of “pure and wholesome water” and “water regulations” in British and American English, 1800 to 2000. (Google 2013)

Conclusions

Pure and wholesome was first used to describe the quality of air, water, milk and food. To be designated as pure and wholesome, these substances had to meet the standards of the day as defined by the human senses. The description of a water as pure and wholesome was one of the first ways that people defined safe drinking water. As we developed analytical methods and an understanding of toxicology, our definition of safe drinking water expanded to include numerical limits placed on individual contaminants. In the U.S., the rise of drinking water regulations has generally replaced the terminology of pure and wholesome, but the term has not disappeared. As long as it is enshrined in legislation and regulation, we will continue to see this artifact of the past used as part of the definition of safe drinking water.

References:

- Ainsworth, H. 1639. Annotations Upon the Five Books of Moses, the Book of the Psalmes, and the Song of Songs, or Canticles. London:M. Parsons, Song Chap. VII, 52.

- “Albany Water Works.” 1815. The American Magazine. 1:5

- Beck, M.B. 1984. “Topic of Public Interest–Water Quality.” J. R. Statist. Soc. A. 147:2 293-305.

- Blake, N.M. 1956. Water for the Cities. Syracuse, NY:Syracuse University Press. 50.

- Berenger, Charles Random de. 1828. “Reflections and appeals which have been presented to the official departments on the Game Laws, etc., the regulations for granting patents for inventions, and the means of securing large supplies of pure and wholesome water, being subjects of great national importance.” Bristol Selected Pamphlets. University of Bristol Library Stable. http://www.jstor.org/stable/60247206 (Accessed: November 24, 2013).

- Daisy, Michael (ed.). no date. “Detroit Water and Sewerage Department: The First 300 Years.” http://dwsd.org/downloads_n/about_dwsd/history/complete_history.pdf (Accessed November 23, 2013).

- Google Books Ngram Viewer. https://books.google.com/ngrams (Accessed November 24, 2013).

- Hill, J.W. 1915. “The Cincinnati Water Works.” Jour. AWWA. 2:1 42-60.

- “Hemlock Lake.” http://www.cityofrochester.gov/article.aspx?id=8589936601 (Accessed November 23, 2013).

- Islam Awakened Qur’an Index. 2013. http://www.islamawakened.com/quran/5/..%5C5%5C88%5Cdefault.htm (Accessed November 24, 2013).

- Kemna, Adolph. 1905. “Purification of Water For Domestic Use—European Practice.” Transactions ASCE. 54:Part D 160.

- Lipsius, Justus. 1584. His Second Book of Constancy. http://people.wku.edu/jan.garrett/lipsius2.htm (Accessed October 8, 2013).

- Magie, William J. 1910. In Chancery of New Jersey: Between the Mayor and Aldermen of Jersey City, Complainant, and the Jersey City Water Supply Co., Defendant. Report for Hon. W.J. Magie, special master on cost of sewers, etc., and on efficiency of sterilization plant at Boonton. (Case Number 27/475-Z-45-314): 1–15. Jersey City, N.J.: Press Chronicle Co.

- MacKenzie, J. 1759. The History of Health and the Art of Preserving It. Edinburgh:William Gordon 103.

- Page, D., O’Leary, G., Boland, A., Clenaghan, C. and Crowe, M. 2002. “The Quality of Drinking Water in Ireland: A Report for the Year 2001.” Environmental Protection Agency (Ireland). 98.

- “Parashat Vayetze – No Tranquility for the Righteous.” Rav Meir Kahane and Binyamin Kahane Torah Blog. http://tzipordror.blogspot.com/2011_11_27_archive.html November 27, 2001. (Accessed November 24, 2013).

- Porter, T. 1661. A Compleat Delineation and Description of the Several Regions & Countries in the Whole World;: Abridged & Comprised in a New Mapp Thereof; Supplied with Easy Rules and Directions, for the Benefit and Pleasure of the Reader. London:Robert Walton 18.

- Sancta Missa. 1962. “Blessings of Places Not Designated for Sacred Purposes.” Missale Romanum. http://www.sanctamissa.org/en/resources/books-1962/rituale-romanum/51-blessings-of-places-not-designated-for-sacred-purposes.html (Accessed October 8, 2013).

- Singer, N. 2013. “In a Scoreboard of Words, a Cultural Guide.” The New York Times. December 8, 2013.

- Stevens, Frederic W. 1908. In Chancery of New Jersey: Between the Mayor and Aldermen of Jersey City, Complainant, and Patrick H. Flynn and Jersey City Water Supply Co., Defendants; Opinion, May 1, 1908.

- Thresh, J.C., Beale, J.F. and Suckling, E.V. 1933. The Examination Of Waters And Water Supplies. Philadelphia, PA:P. Blakiston’s Son & Co., Inc. 90-93.

- Vile, J.R. 2003. Great American Judges: An Encyclopedia. vol. 1. Santa Barbara, CA:ABC-CLIO, Inc. 635.

- Whintringham, C. 1718. A Treatise of Endemic Diseases: Wherein the Different Nature of Airs, Situations, Soils, Waters, Diet, &c. are Mechanically Explained and Accounted for. York, England:Grace White 87.

- Whipple, G.C. 1907. The Value of Pure Water. New York:Wiley 2-4.